How do bacteria use the biofilm to protect themselves from antibiotics, the immune system, and the causes of urinary tract infections – a challenging disease to manage?

Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections (rUTIs) can be defined as experiencing at least 3 courses of infection within the past 12 months or at least 2 courses within 6 months. While UTIs may appear to occur independently, they are often caused by bacteria from the initial infections that have not been completely eradicated. These bacteria can persist even in the presence of antibiotics and can evade attacks from the body’s immune cells by forming protective bacterial biofilms. These bacterial species eventually exit their dormant state and develop a community to cause rUTIs. Another course of antibiotic therapy may eliminate most disease-causing bacteria, but some still persist, protected by the biofilm. This cycle can lead to frequent occurrences of rUTIs.

Figure 1: The model of UTIs-caused bacteria in human

(Source: https://www.vinmec.com/)

Some infections can occur and frequently recur, often observed in urinary tract infections. Approximately % of women with urinary tract infections are estimated to experience recurrence (1). In fact, research utilizing DNA sequencing techniques has identified that about 77% of all recurrent urinary tract infection cases are caused by bacteria surviving after antibiotic treatment in the initial infection (2), and the reason is attributed to bacterial species capable of forming a biofilm.

What is Biofilm?

- coli and some other pathogenic bacteria that invade the urinary tract form a biological membrane, commonly known as biofilm. Biofilm is a protective shield for bacteria, often referred to as a “bacterial city”, where the bacterial community inside this biofilm can remain in a “dormant state” for an extended period, waiting for an opportunity to cause recurrent infections. Bacteria in the urinary tract typically initiate the infection process by adhering to the urinary tract mucosa, which provides them with an ideal surface. Once attached to this surface, they can generate a biofilm.

Figure 2: The bacterial biofilm lifecycle (Source: Bay Area Lyme Foundation)

The biofilm is essentially a slimy matrix composed of carbohydrates, proteins, fats and DNA. This matrix allows bacteria to adhere tightly to each other, forming clusters while also adhering to the urinary tract mucosa, thereby protecting them from the surrounding environment, including antibiotics. Bacteria that cannot form biofilm seem to have a lower likelihood of causing rUTIs. On the contrary, bacteria with the ability to form biofilms become the leading cause of rUTIs.

Biofilm and antibiotic resistance

Why do rUTIs caused by biofilm-forming bacteria become difficult to treat? The biofilm protects bacteria from the human immune system as well as various kinds of antibiotics. Immune cells like white blood cells function by detecting, capturing and eliminating bacteria. However, when encased in the biofilm, bacteria are shielded from the attacks of white blood cells (1).

The biofilm also acts as a protective barrier against antibiotics. Without the ability to penetrate this protective layer, antibiotics cannot eliminate bacteria. The problem becomes even more complex when bacteria inside the biofilm can develop antibiotic resistance to any type of antibiotic that manages to breach the biofilm barrier and reach them. Bacteria have the ability to exchange genes governing resistance and their close association within the bacterial community inside the biofilm enhances this capability (3). Finally, bacteria inside the biofilm can replicate and reproduce or enter a dormant state. Many antibiotics function by targeting bacteria during the replication process. However, if the bacteria are in a dormant state, the antibiotics will not be effective.

Other mechanisms causing urinary tract infections

Unfortunately, rUTIs can become more complicated. The biofilm is a key mechanism that allows bacteria to evade detection, and it is perhaps the most common mechanism, but there may be other mechanisms as well. Bacteria can also invade the bladder tissue and form Quiescent Intracellular Reservoir (QIR), where they can lie dormant within the cells of the tissue and act as a population, leading to new infections. The cells on the surface of the urinary tract are renewed in cycles. As these cells die and are shed, the QIR is released and can cause a new episode of infection (1).

The QIRs existing within cells can trigger immune responses and urinary tract inflammation symptoms, but due to their hiding within cells, immune cells often struggle to detect them. Moreover, there may be no bacteria present in the urine sample, leading to negative culture results. This can also provide a plausible explanation for Interstitial Cystitis (IC) – a condition characterized by symptoms similar to rUTIs, with negative test results in microbial cultures from urine samples.

Biofilms are not only present in the urinary tract.

The biofilms are not only present in the urinary tract. According to the US National Institute of Health (NIH), biofilm-forming bacteria are associated with 80% of infection cases, with the urinary tract being one of the primary areas where biofilms can become a serious concern (4). For example, dental plaque caused by bacteria in the mouth is a form of biofilm. Biofilms can also develop during vaginal infections, such as Bacterial vaginosis (BV), contributing to the difficulty in treating recurrent bacterial vaginosis episodes.

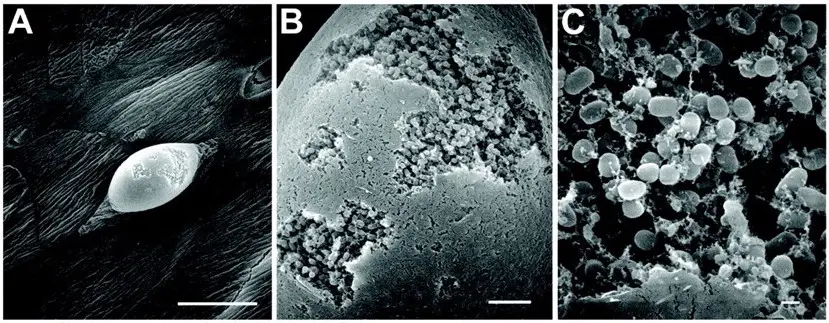

Figure 3: An electron microscope images on the surface of the mouse bladder with urinary tract infection reveal large intracellular biofilm clusters within the bladder surface. The uninfected spots appear smooth, while the infected spots have rough patches on the surface (Source: The Marshall Protocol Knowledge Base)

Biofilm processing

Unfortunately, current antibiotic treatments hardly effectively address biofilms. More research and developments are needed for a more efficient alternative approach. Biofilms and QIRs have a high likelihood of forming as bacterial populations increase and the infection progresses. This provides additional opportunities for bacteria to form populations enclosed within a biofilm, and invade surrounding tissues. The likelihood of recurrent urinary tract infections will decrease if acute urinary tract infections are treated promptly and not allowed to progress into chronic stages.

References

- Glover M, Moreira CG, Sperandio V, Zimmern P. Recurrent urinary tract infections in healthy and nonpregnant women. Urol Sci. 2014;25(1):1-8. doi:10.1016/j.urols.2013.11.007.

- Ejrnæs K. Bacterial characteristics of importance for recurrent urinary tract infections caused by Escherichia coli. Dan Med Bull. 2011 Apr;58(4):B4187. PMID: 21466767.

- Delcaru C, Alexandru I, Podgoreanu P, et al. Microbial Biofilms in Urinary Tract Infections and Prostatitis: Etiology, Pathogenicity, and Combating strategies. Pathogens. 2016;5(4):65. Published 2016 Nov 30. doi:10.3390/pathogens5040065.

- Sara M. Soto, “Importance of Biofilms in Urinary Tract Infections: New Therapeutic Approaches”, Advances in Biology, vol. 2014, Article ID 543974, 13 pages, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/543974.

- Machado D, Castro J, Palmeira-de-Oliveira A, Martinez-de-Oliveira J, Cerca N. Bacterial Vaginosis Biofilms: Challenges to Current Therapies and Emerging Solutions. Front Microbiol. 2016;6:1528. Published 2016 Jan 20. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.01528.

- https://uqora.info.