Probiotics for Skin – What We Should Know?

Recent studies have provided increasing evidence to prove that gastrointestinal microorganisms play a crucial role in regulating systemic inflammation and skin-related conditions. The latest updated scientific evidence has shown that oral probiotics can support the treatment of certain skin conditions, such as acne, allergenic dermatitis, sunlight-caused aging, psoriasis, and wound healing [1].

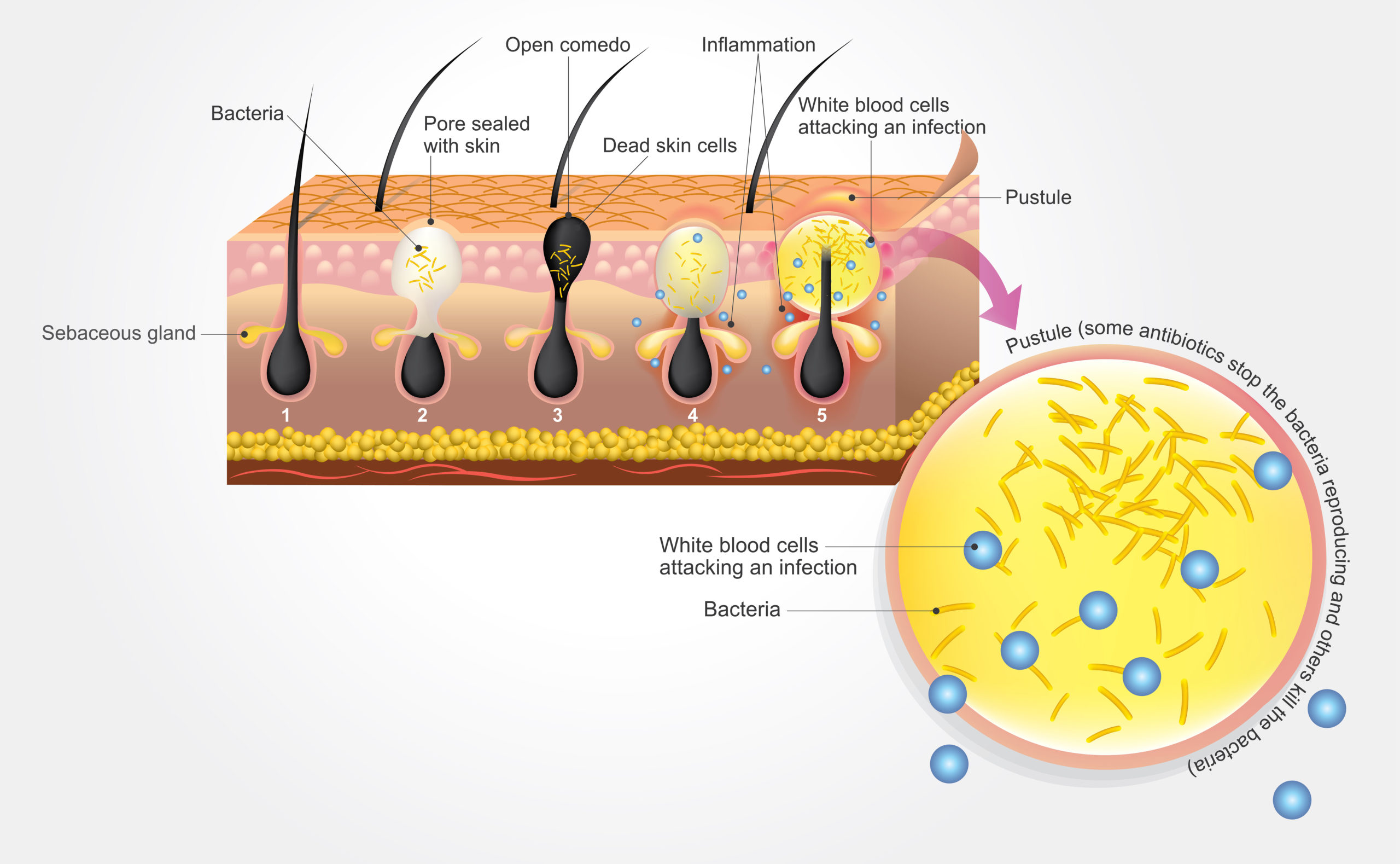

Acne is one of the most common skin conditions, affecting approximately 85% of people in their entire life (Figure 1). There are various factors that cause acne, such as alterations in the follicular keratinization process, increased and altered sebum production under the influence of androgens, invasion of Propionibacterium acnes in the hair follicles, and complex inflammatory mechanisms involving both innate and adaptive immunity [2].

Figure 1: Acne formation in the skin.

There is scientific evidence suggesting that the interaction between skin bacteria and the host’s immune system plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of acne dermatitis. Propionibacterium acnes is commonly found in sebum-rich areas and is a part of the skin microflora, interacting with other normal skin microorganisms such as Staphylococcus cholermidis, Streptococcus pyogenes and Pseudomonas sp. Its overgrowth has long been believed to contribute to the development of acne [3].

The skin microflora of acne patients differs from that of non-acne individuals. Those with acne have distinct features, and systemic antibiotic use can modify the skin microflora, altering its composition and diversity, especially concerning P. acnes, which correlates with the severity of acne. Current challenges in acne treatment include adherence to topical treatments, which can disrupt the skin barrier, leading to dryness and irritation. Research by Park et al., has suggested that probiotics can alter some factors in the pathophysiology of acne development and may also improve adherence [4].

How do Probiotics Benefit Skin Health?

The relationship between gut microflora and acne has attracted attention. Authors of recent studies have focused on the gut-brain-skin relationship and the immunobiology of acne, proposing the hypothesis that stress affects the gut microflora, leading to skin inflammation and consequently acne. Dietary adjustments and probiotics can potentially modulate the gut microbiota and improve acne [5].

In 1912, a published study in the Journal of Cutaneous Diseases for the first time reported that “bacterial therapy on-site” may be effective in treating various skin disorders, including acne dermatitis [6].

The term “bacterial therapy” is currently resurfacing in the scientific community, encompassing various types of bacterial products and application methods related to isolated or diverse bacteria species. It can be broadly used to describe any use of bacteria or bacterial components for therapeutic benefits, not limited to probiotics but also including enzymes derived from bacteria and bacterial culture [6,7].

The Promising Role of Probiotics for Skin and Acne Treatment (Science-Backed)

The beneficial effects of directly applying lactic acid bacteria to the skin have been studied for many decades. Di Marzio and his colleagues demonstrated that Streptococcus thermophilus, which can be found in yogurt, can increase ceramide secretion when applied topically to the skin for 7 days [8]. Bow and his colleagues emphasized that this is related to the treatment of acne, especially when certain ceramides (e.g., phytosphingosine) are believed to provide both antibacterial activities against P. acnes and anti-inflammatory properties [9].

The topical application of phytosphingosine has been shown to reduce oiliness and pustules in acne patients [10]. An in-vitro study evaluated the symbiotic potential of bacteria and konjac glucomannan hydrolysate (GMH) to inhibit the growth of P. acnes. The authors found that different bacterial strains could inhibit the growth of this skin bacterium, and the presence of prebiotic GMH significantly enhanced the inhibition [11].

A strain of lactic acid-producing bacteria isolated from human fecal samples and identified as Enterococcus faecalis SL-5 showed antibacterial activity against Gram-positive bacteria, especially P. acnes. Skin cream containing E. faecalis significantly reduced pustules compared to placebo creams. Kang and his colleagues suggested that the anti-P. acnes effect of E. faecalis SL-5-produced compounds could potentially play a role in the treatment of acne and serve as an alternative to topical antibiotics [12].

Another strain that has shown the ability to inhibit P. acnes is Streptococcus salicylic, a prominent member of the oral microflora in healthy humans. In addition to anti-bacterial properties, it also can act as an immunomodulatory substance to inhibit various inflammatory pathways [13,14].

Figure 3. Role of Probiotics for Skin and Acne Treatment

Lopes and colleagues performed a study to assess the abilities of various probiotic strains to adhere to human skin and their antibacterial activities against selected pathogens. They also evaluated the surface-associated compounds known as cell-free culture supernatants (CFCS) of these probiotic strains for their ability to prevent the formation or disrupt the biofilms established by the selected pathogens and to identify potential representative antimicrobial compounds.

The author found that the antibacterial activity of CFCS from the selected probiotic strains was observed Escherichia coli, P. acnes , and Pseudomonas aeruginosa; however, none of the strains could inhibit the growth of Staphylococcus aureus [15].

Allergic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic skin condition that can cause severe itching and scaly damage. Current treatment methods for AD patients include healing and protecting the skin barrier with moisturizing creams, anti-inflammatory drugs, anti-histamines, biologics like dupilumab, and localized or systemic antibacterial therapy [16].

Because these traditional treatments may not be sufficient for some patients or may have side effects, alternative non-drug treatment methods, such as probiotics, are being researched to address this skin condition [15,17]. Additionally, one of the latest trends in skincare to combat skin aging is using probiotics.

Recently, primary research on animal models and clinical trials in humans has shown that probiotic products have multiple effects on skincare. Research by Milad and colleagues demonstrated that B. subtilis derivative can promote the ability to heal wounds [18]. In the study of Lu and colleagues, the effects of surfactin A isolated from B. subtilis have been addressed in wound healing, angiogenesis, cell migration, inflammatory reaction, and scar formation.

These results showed that 80.65 ± 2.03% of wound being treated with surfactin A was closed/sealed, while 44.30 ± 4.26% of wound areas treated with a placebo remained unhealed on the 7th day (P < 0.05). Mechanistically, surfactin A regulates the downregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), promoting keratinocyte migration through mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB ) signaling pathways, regulating the pre-inflammatory cytokine secretion and macrophages phenotype transformation.

Specifically, surfactin A demonstrates the ability to inhibit scar tissue formation by affecting the expression of smooth muscle α-actin (α-SMA) and transforming growth factor (TGF-β) [19].

What does LiveSpo offer?

On the current market, there is a probiotic product named LiveSpo® Skin Fresh (Figure 4), formulated as a liquid suspension containing pre-activated live spores of Bacillus sp. for supportive treatment of acne and skincare.

Figure 4. LiveSpo® Skin Fresh

Effects of LiveSpo® Skin Fresh in acne treatment:

- Reduce inflammation: Create a healthy bacterial balance on the skin to reduce inflammation.

- Enhance the skin’s natural moisture: Eliminate redness, sensitivity, breakouts, and irritation.

- Produce antimicrobial substances that inhibit the growth of P. acnes, a bacteria responsible for acne.

- Protect the skin from environmental damage: Eliminate harmful microorganisms.

Two strains of B. subtilis ANA46 and B. clausii ANA39 in LiveSpo® Skin Fresh have undergone genetic sequence analysis. The results show that both strains do not contain any genes encoding toxins or allergenic factors. Besides, genes responsible for antibiotic resistance are located on the chromosome, not on a plasmid, indicating that they are not able to transfer to other strains. Therefore, they are considered safe for human use.

References

-

- França, K. (2021). Topical probiotics in dermatological therapy and skin care: a concise review. Dermatology and therapy, 11(1), 71-77.

- Tan AU, Schlosser BJ, Paller AS. A review of diagnosis and treatment of acne in adult female patients. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;4(2):56–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.10.006.

- Platsidaki E, Dessinioti C. Recent advances in understanding Propionibacterium acnes (Cutibacterium acnes) in acne. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.15659.1.

- Park SY, Kim HS, Lee SH, Kim S. Characterization and analysis of the skin microbiota in acne: impact of systemic antibiotics. J Clin Med. 2020;9(1):168. doi: 10.3390/jcm9010168.

- Lee YB, Byun EJ, Kim HS. Potential role of the microbiome in acne: a comprehensive review. J Clin Med. 2019;8(7):987. doi: 10.3390/jcm8070987.

- Peyri J. Topical bacteriotherapy of the skin. J Cutaneous Dis. 1912;30:688–689.

- Hendricks AJ, Mills BW, Shi VY. Skin bacterial transplant in atopic dermatitis: knowns, unknowns and emerging trends. J Dermatol Sci. 2019;95(2):56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2019.07.001.

- Di Marzio L, Cinque B, De Simone C, Cifone MG. Effect of the lactic acid bacterium Streptococcus thermophilus on ceramide levels in human keratinocytes in vitro and stratum corneum in vivo. J Investig Dermatol. 1999;113:98–106. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00633.x.

- Bowe WP, Logan AC. Acne vulgaris, probiotics, and the gut–brain–skin axis—back to the future? Gut Pathog. 2011;3(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-3-1.

- Pavicic T, Wollenweber U, Farwick M, Korting HC. Anti-microbial and -inflammatory activity and efficacy of phytosphingosine: an in vitro and in vivo study addressing acne vulgaris. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2007;29:181–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2494.2007.00378.x.

- Al-Ghazzewi FH, Tester RF. Effect of konjac glucomannan hydrolysates and probiotics on the growth of the skin bacterium Propionibacterium acnes in vitro. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2010;32(2):139–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2494.2009.00555.x.

- Kang BS, Seo JG, Lee GS, Kim JH, Kim SY, Han YW, et al. Antimicrobial activity of enterocins from Enterococcus faecalis SL-5 against Propionibacterium acnes, the causative agent in acne vulgaris, and its therapeutic effect. J Microbiol. 2009;47:101–109. doi: 10.1007/s12275-008-0179-y.

- Bowe WP, Filip JC, DiRienzo JM, Volgina A, Margolis DJ. Inhibition of Propionibacterium acnes by bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances (BLIS) produced by Streptococcus salivarius. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:868–870.

- Cosseau C, Devine DA, Dullaghan E, Gardy JL, Chikatamarla A, Gellatly S, et al. The commensal Streptococcus salivarius K12 downregulates the innate immune responses of human epithelial cells and promotes host-microbe homeostasis. Infect Immun. 2008;76:4163–4175. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00188-08.

- Lopes EG, Moreira DA, Gullón P, Gullón B, Cardelle-Cobas A, Tavaria FK. Topical application of probiotics in skin: adhesion, antimicrobial and antibiofilm in vitro assays. J Appl Microbiol. 2017;122(2):450–461. doi: 10.1111/jam.13349.

- Catherine Mack Correa M, Nebus J. Management of patients with atopic dermatitis: the role of emollient therapy. Dermatol Res Pract. 2012;2012:836931. doi: 10.1155/2012/836931.

- Di Marzio L, Centi C, Cinque B, et al. Effect of the lactic acid bacterium Streptococcus thermophilus on stratum corneum ceramide levels and signs and symptoms of atopic dermatitis patients. Exp Dermatol. 2003;12:615–620. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2003.00051.x.

- Shahsafi, M. (2017). The effects of Bacillus subtilis probiotic on cutaneous wound healing in rats. Novelty in Biomedicine, 5(1), 43-47.

- Yan, L., Liu, G., Zhao, B., Pang, B., Wu, W., Ai, C., … & Shi, J. (2020). Novel biomedical functions of surfactin A from Bacillus subtilis in wound healing promotion and scar inhibition. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 68(26), 6987-6997.